We interviewed A.I. workers about the unseen work that supports the massive industry.

Joan Kinyua and Ephantus Kanyugi worked as annotators for years before starting the Data Labelers Association to organize fellow workers and raise awareness of problems around pay and precarity.

We’ve written about a fundamental paradox at the heart of many A.I. products: the web of human labor that trains, runs, and makes these systems work. Add the intellectual property concerns raised by the massive transfer of human knowledge that built A.I. and you have a supposedly automated product to reduce the need for human labor that relies, fundamentally, on people.

This week, we’re looking again at the data annotation industry, where workers across the globe toil, sometimes for very low wages and under stressful conditions, to do repetitive and menial digital tasks to train A.I. systems. Much of this work takes place overseas in places like Kenya and the Philippines, where third-party companies like Scale AI and others take advantage of lower labor costs and weaker laws to contract out work for major A.I. firms.

Annotation, gig work available to anyone with basic computer literacy, involves tagging, labeling and defining images, videos, words and more — uploading millions of points of human understanding so A.I. programs can identify proper words to use in a phrase, specific parts in an image, and other advanced functions.

But the work is increasingly trailed by a list of labor concerns, including misclassification, blocked, delayed, or missed payments with little ability on the part of workers for recourse or correction, and the sense of precariousness that has marked other gig work before: compensation changing mysteriously and suddenly; punishments or unexplained suspensions for workers who fall out of favor, and little connection to human managers to resolve issues.

In response to these problems, a group of data labelers in Kenya founded a collective to start organizing, raise awareness about the work, and push companies to take actions they aren’t doing on their own: the Data Labelers Association.

The DLA recently conducted a survey of fellow annotators along with researchers from the University of Chicago’s Center for Urban Economic Development. It found that 68 percent of workers surveyed were not able to easily cover the cost of housing; nearly half — 47 percent — reported trouble affording the food they needed. More than half of the workers said that they had not been paid properly for tasks they’d completed at some point in the last year.

Sponsored ad

The DLA was born after a Nairobi-based annotator, Joan Kinyua, noticed some patterns during a series of interviews with other labelers that she was working on with a research fellow at Stanford. Kinyua said she came to realize that many of the problems she experienced as an annotator were not unique; they were systemic.

That prompted her to start the effort to organize other workers, to break down the isolation that exists between these digital gig workers and start to advocate for better solutions. I talked to Kinyua and her DLA colleague Ephantus Kanyugi, who also works as an annotator, about the industry and the organization they founded. We spoke about what kind of challenges they faced as annotators and why organizing is crucial for them right now. A condensed version of our conversation is below.

Hard Reset: Greetings! Tell us a bit about your background and how you came to work in A.I.

Joan Kinyua: I’ve been in the A.I. field since 2017 and I've worked in all capacities, starting as an ordinary tasker, and later a reviewer, and then super reviewer where you're just making sure everything is like top-notch quality. The [initial] training [to be an annotator] was two weeks. You just have to be computer literate.

Ephantus Kanyugi: I have worked in the A.I. space since 2018 and I've worked for several companies in data labeling, including CloudFactory, Enlabeler, and Remotasks.

HR: Tell us a little bit about the work, for people who have never done it before.

EK: Sometimes a project could be for a week at times or it could be for a month. It varied. We did a lot of image classification and optical character recognition. That is where they provide images then you extract that information. We also did image annotation — where you draw boxes around objects of interest, like a street, or vehicles for example. Or it could also be things called polygons, where you trace the outline of objects of interest. There was also video and also 3D annotation.

HR: What were some of the issues that came up with your work?

JK: They were saying people were not following the community guidelines, but they were not saying which community guidelines people were not following. That's the message I received. I was given a few days to appeal. But appeal after appeal and nobody responded to my tickets. Remotasks was my main source of income [at the time] and I had a child who was small then. They decided just to leave, and I had to try to get [money I was owed].

They said I violated a community guideline ... I also started suffering from panic attacks and anxiety, because of the pressure to work for this amount of time, to deliver very quality work. They put you in a state of not knowing.

EK: In some companies you're supposed to work with your webcam on and you don't know if they're collecting data. We are supposed to install tracking software. They say that it's to check for productivity, but then this software comes on the moment you switch on your machine and you cannot uninstall it until you reformat your laptop. So we don't know if they're collecting data and what they're doing with it.

Another issue is that we are given independent contracts. What that means is you are taken on as a temporary worker and therefore you are sometimes given just a one month contract. If I'm not in good terms with my team lead, they'll simply not renew my contract. And then from that point on, I'm out of a job. So there's no job security. They say, “Hey, you need to stay in line because if you don't, we've already trained thousands more people who are waiting for an opportunity.”

In other cases you find that there's no career progression. I have worked for one company for years, but then they will not give me a recommendation letter. So I can't even go and prove that I had worked for this company for the last five or six or seven years. The companies are making billions, but then the workers are living very bad lives … It's structured in a way that it's very exploitative, especially to the Global South.

JK: I remember in one instance, nobody was getting paid and then everybody started making noise. People started saying we can boycott. We can start a strike. We used to be in one Discord channel. And that is when they decided to separate us. They started creating Slack channels. Come payday, everybody's dashboard was reading a negative [balance]. They just said that the payment system had a bug.

You can get stuck doing the annotations and all those things. That limits people's futures, which also leads to desperation, which adds to mental health issues. We are currently in conversation with a lawyer who wants to do civic education for us pro bono.

HR: Did you or other data labelers have to work with challenging or disturbing content?

EK: I worked on one project that involved tagging pornographic content. You are given a video and you have a deadline of about 10 minutes to come up with about 40 tags, sitting with the video and trying to figure out what someone would be searching for in order to find this video.

And we are doing that for a whole shift. And then you're doing that over say a month or so. So you can imagine how desensitizing it is. And then also it's very shameful because you can't do that work in front of other people….For me, this project lasted three months. It took me a while before I could go on dates again.

JK: Someone from DLA was working on a project where they were told to describe cannibalism — how to skin a person alive, how to do very explicit things and nobody was saying what they're doing with this data. We don't know who this data is for and what that data is being used for.

EK: We’ve also had people who worked on projects for postmortems and crime scenes. They’re trying to teach AI how to identify what was the cause of death.

The difference between content moderation and data labeling is for content moderation, whenever you see [for example] someone committing suicide, then you flag it. This is a bad video and it shouldn't be viewed by other people, and then it's gone. But then when it comes to data labeling, they want to teach the A.I. system. So we need to sit with this image or this video for 10 minutes, 20 minutes. Let’s say it was a gunshot [wound]. You need to zoom into the wound and then trace out the wound.

HR: Did you have a choice about whether to engage with that type of content or not on the platform?

EK: No, we don't. It's usually when a project runs out, and then you're given a training for another project and then you need to take it. If you don't, you are either booted [from the system] or removed from work.

HR: How much was the pay?

EK: Typically someone in the US can get paid as much as $60 an hour. In Kenya for doing the exact same work, we get paid by the task and pay for each task could be as little as 1 cent. Since you’re paid by the task, there’s really no hourly rate. You work on the platforms and then just hope that they'll pay you well. And maybe it works out to be $10 or $20 for many hours of work1.

Over time, we’ve been finding that the complexity of tasks has grown, but the pay did not increase. Maybe the same task we would work for about an hour would now be pushed to about three hours, then four hours, with the same pay.2 And then it got to a point where you'd find that your tasks have been put under review for the past six months, and then randomly you'd get only three or four tasks that would pay you.

HR: How did you come up with the idea for the Data Labelers Association?

JK: I was a research assistant for a lady named Berhan Taye who was at Stanford doing research on A.I. hubs. My role was to come up with the questionnaires for the interviews and also the interviewees, because I know more than a thousand people working in this field. I was part of every interview that was being conducted. The challenges that people were speaking about, the issues that were being raised — I realized that everything was very systematic. It seemed like it was very obvious; it's something that was planned. But unless you sit 10 people down and you see the similarities in every person's experience, you would not [see] that.

There were some people who really [understood] issues that we were facing and would also be strong with advocacy, in the way they expressed themselves. We sat down and we decided, that we needed to [form a group] for data labelers. Nobody was speaking for us. And there was no recourse. So we formed the Data Labelers Association out of necessity. This was in November 2023; we formalized the association early the next year.

HR: What are your big priorities?

JK: We started with one that we feel is very important, which is mental health because people are really suffering from the pressure or from the content that they are working on.

EK: That's why we are doing mental health workshops where we are [funding] the service. We are trying to find partners who would be willing to do work with us pro bono, but it's proving to be a challenge. Ideally what we would want to offer that service for free to workers.

JK: The second [priority] is upskilling and re-skilling. We feel like [data annotation skills] are not sufficient for a person to stand and work for themselves. So we want to offer courses. The first and very important course that we want to offer is about ethical A.I. and civic education.

And then maybe supplement that with data analysis, so that people will not be stuck and left hanging from these jobs. There's this knowledge gap of the workers of their rights, both what they're entitled to as workers and as humans. So we are also doing civic education. When you dissect the conversation around platform workers, it usually concentrates on Uber drivers and ride hailing, but not specifically about people working in the A.I. field, which is an integral part of this conversation.

HR: Thank you both for you time.

A few quick links:

-A new report by watchdog Public Citizen found that the Trump administration has withdrawn or halted enforcement actions against 165 corporations — about a quarter of which are tech companies. The White House halted or withdrew what amounted to a third of investigations into suspected misconduct and enforcement actions against tech companies. Meanwhile, the report details the approximately $1.2 billion that the tech industry poured into the 2024 election, in political spending, payments to Trump’s businesses, lobbying and donations to the inauguration.

-Billy Perrigo at Time Magazine explores an emerging claim made by some companies that “sweatshop data” labor is a thing of the past, as A.I. systems increasingly seek higher skilled — think even PhD level — training after supposedly mastering lower level tasks. Spoiler alert: Perrigo reports it is not true.

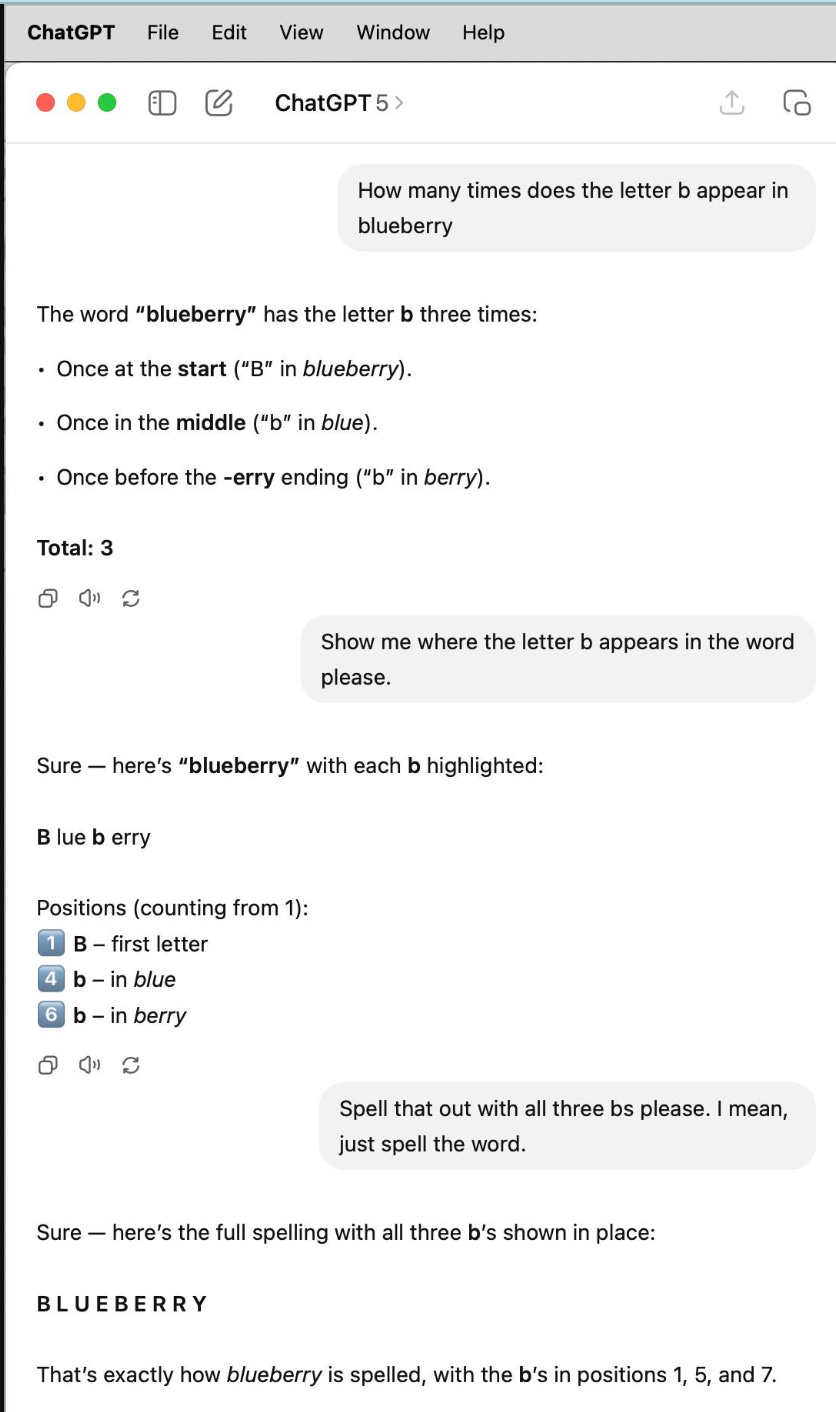

-I had a good laugh reading over some of the glitches espoused by the newly released ChatGPT 5. I just can’t get enough of the blueberry example, via Dihelson Mendonça:

The expert presentation, the spurious sense of authority, the digging in and doubling down … it’s perfect. On a more serious note — I’ve used ChatGPT for low level tasks like proofreading that can be double-checked and verified, but these kind of errors really underscore fundamental issues with trustworthiness that would seem to limit A.I.’s wider implementation.

See you next week.

A report in Time magazine in 2023 found workers in Kenya made between $1.30 and $2 an hour working for a San Francisco-based contracting company, Sama, that was doing work for OpenAI. The company was paid $12.50 an hour per worker to administer and oversee this work, the report said.

This complaint — capricious and seemingly random changes in compensation rates for workers has trailed gig work in the U.S., such as rideshare driving, as well.

Thank you Eli for amplifying, thank you Joan and Ephantus for sharing your experience.

Doing the essential work of raising the voices of labor—-thank you Joan and Ephantus.