Why Are There So Few Big Tech Comms Whistleblowers?

The cultiness is real.

In 2018, I briefly worked for a “decentralized blockchain project” that I later realized had a north star of pumping a crypto token price rather than creating real usable apps for people. It would be my last real job in tech.

After being told I was “terrible at my job” by colleagues because I was asking too many questions—and then breaking out in hives and losing my voice when I was isolated and told “no one wants to work with you”—I signed a severance agreement with the blockchain engineers, and I received two-months’ pay. Part of this severance agreement was a non-disparagement clause.

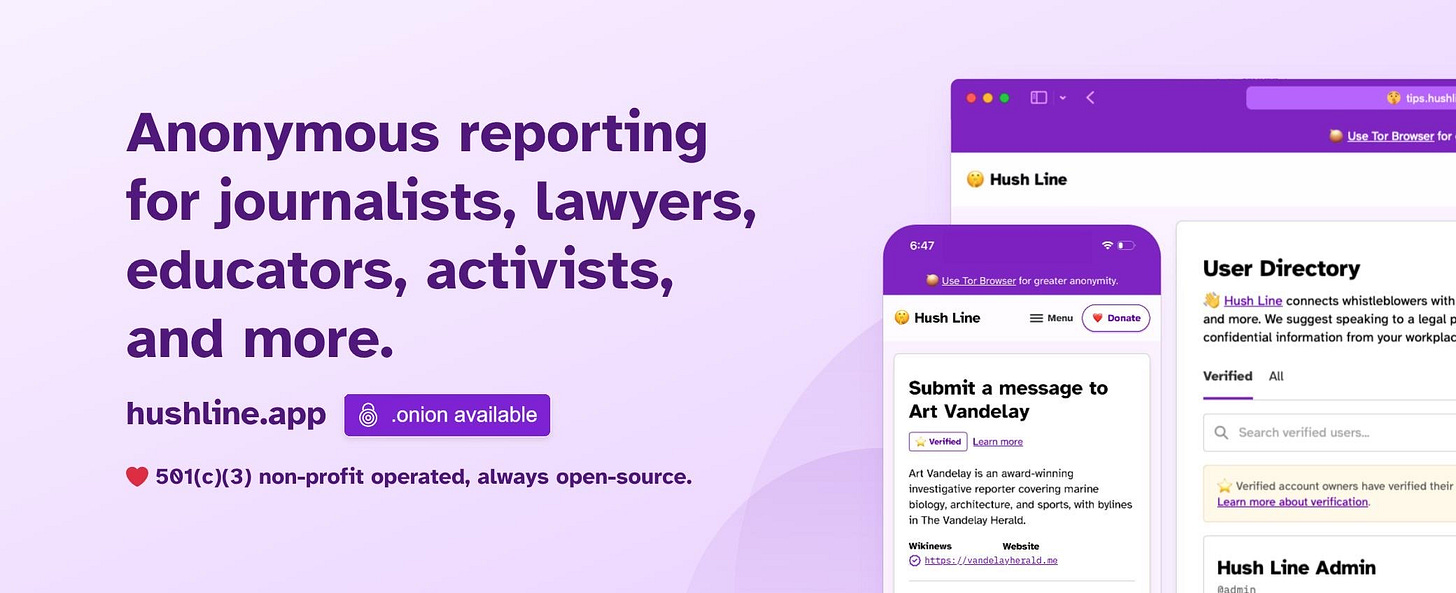

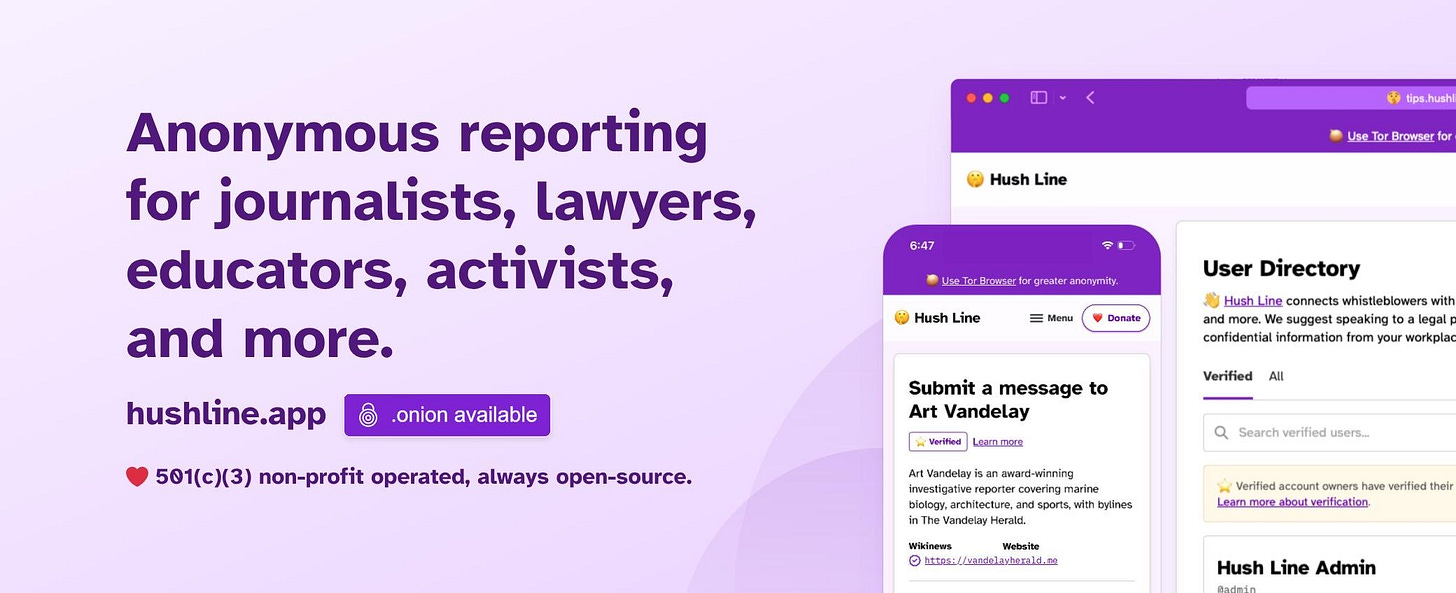

AD: Hush Line is a platform that provides individuals and organizations with open-source, end-to-end encrypted, anonymous tip lines.

I had no clue I had any sort of leverage in the world, and was scared. So I followed the advice of an independent lawyer who said I should make it a “mutual non-disparagement” clause and leave it at that.

Years later, I learned a lot about employment law, and also the power of story to change culture. When a freelance reporter was working on a piece about women in male-dominated environments for the Washington Post, I responded to her request for stories and shared mine. I technically broke my non-disparagement clause in order to do so.

I was not sued, nor even threatened. Maybe they didn’t see it. But in general, it is incredibly rare for a company to sue someone for breaking their non-disparagement clause. This is because if it’s something damning, they probably don’t want to draw more attention to it. Beyond this, if it becomes public record that they have sued for non-disparagement, the general public is usually on the side of the person sharing their human story—not with the lawyers and communications teams carefully crafting their vague remarks.

It also makes people feel generally uncomfortable as human beings. Imagine being censored from ever being able to talk negatively or even in a more nuanced way about a bad boss or workplace? Venting about work and bosses is something that is so central to our lives, the idea of a surveillance state where we can’t even say “I didn’t like so-and-so” seems dystopian.

Meta departed from this norm recently, choosing to hold former policy director Sarah Wynn-Williams to a non-disparagement clause she signed after she published a memoir about her time at the company. An arbitrator upheld that she must abide by the gag order and no longer promote the book—though the book is experiencing the “Streisand effect,” or renewed focus on something as a result of the attempted cover-up of it. Careless People has catapulted to the top of bookseller lists, and it is everywhere on my TikTok feed.

Wynn-Williams could technically not obey. But to break a gag order being enforced by a court could mean hundreds of thousands of dollars of sanctions. And corporations, who can afford to pay fines and fees if they misbehave or break the law, are relying on the fact that the average person is not willing to pay off court sanctions for “breaking the law” (especially, in this case, if the book is just promoting itself).

It’s especially rare for Wynn-Williams to do what she has done as a communications and policy lead with direct access to executives. Frances Haugen, for example, was a product manager who came across documentation. When you work in communications at a tech company, the cultiness becomes all the more apparent. You are supposed to have a one-track mind, to be on a unified team, to not betray your friends and colleagues. You are the ones defending why the company or product should exist in the first place. And most people don’t see financially or psychologically why they would stray.

Wynn-Williams is interesting not simply because she wrote a memoir about her employer, as others have. Her role and proximity to executives make it all the more interesting that she would choose to call them out. It makes me wonder whether big employers would enforce non-disparagement clauses with other communications and policy officials the same.

AD: Hush Line is a platform that provides individuals and organizations with open-source, end-to-end encrypted, anonymous tip lines.

Some links i’ve been reading:

Hundreds of artists signed a letter calling on the White House to stop Tech Cos from robbing their content for AI training models. It’s quite the impressive list. I’m hoping to see creatives, musicians, publishers, and others join together to make sure people who make content come together to ensure fair payment for content.

Ashley Burch, a prominent voice and performance actor, for one of Playstation’s biggest games, took to Tiktok to voice her concerns about AI usage of her likeness: “I feel worried about this art form,”. Ashley is on strike with SAG-AFTRA but the strike doesn’t seem to be stopping gaming corporations from moving fast and taking things without fair payment.

The Tech Barons are now using God to justify all the bad things. Wired has a fascinating read out from a prayer event with Trae Stephens, one of the Palantir bros, where he claims being an arms dealer is a calling from God. You may laugh, but this is one to watch — pointing to God as justification can enable people to excuse the worst behavior imaginable.