Who Pays for AI’s Power Hunger?

Data centers are driving up electricity prices, draining water supplies, and sparking local revolts—just as Congress moves to make them harder to stop.

To answer billions of queries each day, LLM makers require football-field sized buildings full of servers to plow through the math, the electricity needed to power all those servers, and the millions of gallons of water needed to keep them cool.

As a result, the threat that always-on data centers pose to electricity costs and to water levels is setting off waves of local protest, and state and city officials are stepping in to slow things down.

In Maryland, construction of a new data center stopped in October so officials there could investigate its health and environmental effects. In Northern Virginia—the beating heart of U.S. data-center growth—residents last month openly mobilized against new data center campuses and the grid infrastructure that comes with them. And this week, a Phoenix suburb that had drawn national attention as a battleground over the power of AI companies to build where they like voted down a new center there. As the vice mayor put it to Politico, “what’s in it for Chandler?”

One thing that’s clearly in it for the residents is higher electricity costs. Bloomberg found that wholesale prices for electricity in areas near data centers have risen as much as 267% in the last five years, and the Energy Information Administration, a federal agency, reports that the average residential retail price of electricity for all Americans has risen more than 7% on average in the last year.

Why? A 2025 University of Michigan study is one of several that blames not just the long-term power agreements that companies strike, which reduce supply and drive up prices directly, but also the shared cost of the new infrastructure a regional utility has to add to provide what’s needed. Even a small data center can pull as much power as roughly 2000 homes, but consider that’s 2000 homes in which the lights never go out and every appliance is always on, meaning peak demand on the grid rises at all hours of the day, necessitating the purchase of new wires, new poles, and even new power plants.

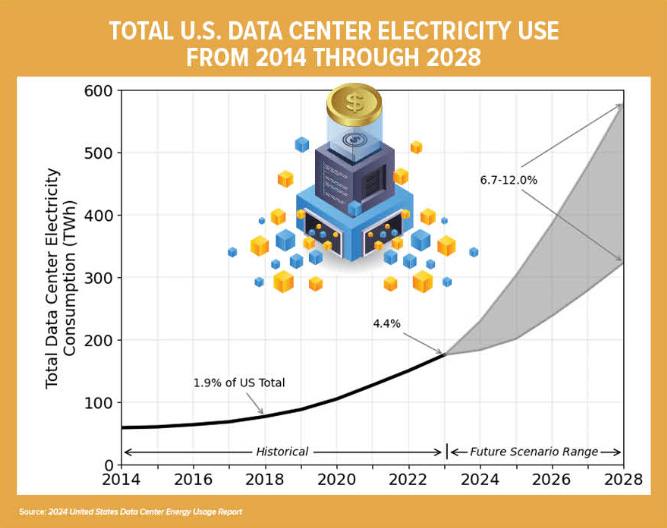

And the new, AI-specific data centers coming online are expected to consume more electricity. Much more. Michael Thomas, the founder of energy-tracking firm Cleanview, whose work is the basis of an alarming Washington Post story about the next generation of data centers, wrote on X that while current data centers “used as much power as a small town…today’s are expected to use as much as a city with 500,000 people. But the largest ones could use as much power as Philadelphia (population: 5.7m).”

This week three Democratic senators announced they’d be investigating these cost increases, writing that tech companies should “pay their fair share of their electricity rates” and “a greater share of the costs upfront for future energy usage”. And yesterday Bernie Sanders went as far as posting a video calling for a moratorium on AI data centers to “give democracy a chance to catch up.”

In response, venture capitalist and Chair of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology David Sacks accused the Senator of “stopping progress completely so China wins the AI race,’ and Elon Musk posted that “takers like Bernie will eventually follow the makers.” The issue has made strange political bedfellows, with Florida governor Ron DeSantis boasting that his recent legislative moves mean “Floridians will not be forced to subsidize Hyperscale AI Data Centers.”

Still, this week the House pushed ahead with the SPEED Act, which would streamline federal rules for approving new energy projects, and would limit the ability of regulators to consider the broader environmental impacts and downstream financial effects of new data centers.

One added complication that may soon give local municipalities added reason for concern: the business of building data centers might not be a stable one. Oracle’s primary private backer of its AI data center plans just pulled out of a deal to building in Michigan, according to the FT, which reported that “lenders pushed for stricter leasing and debt terms amid shifting market sentiment around enormous AI spending including Oracle’s own commitments and rising debt levels.”

Part of the uncertainty is that the data center business is increasingly a business of temporary leases, rather than long-term commitments. This week billionaire real estate developer Fernando de Leon told CNBC that he’s staying out of the sector entirely because he doesn’t trust the financials — especially the tendency of big AI companies to lease, rather than own, the data centers they need.

“I see large technology companies, the largest companies on the planet, with $4 trillion market cap, saying, ‘I don’t want to own this asset. I don’t want to have this on my balance sheet.’ So I ask, Why? Why doesn’t the largest company in the world want to own its own asset?” de Leon said in his CNBC interview.

Sponsored ad

Omidyar Network is hiring a Head of Communications, based in San Francisco, to lead strategic communications. If you or someone you know would be a fit, please apply or share the link!