He Blew the Whistle on Amazon’s Growing Legion of Robots. He Didn’t Expect What Happened Next.

A whistleblower alerted the FTC about the "reverse-acquihire" of Covariant AI, a cutting-edge startup. A year later, Amazon has rapidly developed robots with human-like reasoning.

The whistleblower was feeling hopeful.

It was January 18, 2025. He opened his laptop to a Washington Post article about Covariant AI, a robotics company that had recently been stripped for parts in a “reverse acquihire” orchestrated by Amazon. Details from the whistleblower’s complaint to the Federal Trade Commission and other relevant agencies served as the basis for the article. In the whistleblower’s view, Amazon’s reverse acquihire—a legally untested business tactic where Big Tech recruits top talent from a smaller company and also obtains a license to utilize the smaller company’s technology, but doesn’t purchase the smaller company outright—was a brazen attempt at skirting antitrust regulations.

The whistleblower worried about the implications of Amazon’s reverse acquihire, which could allow the multinational giant to shore up the best robotics talent and software in the world. What would that mean for warehouse jobs? Or other jobs threatened by automation?

The whistleblower wanted his allegations to be publicized before Donald Trump’s inauguration on January 20. In a leaked memo, incoming FTC Chair Andrew Ferguson had already pledged to “reverse Lina Khan’s anti-business agenda” and “stop Lina Khan’s war on mergers,” he wrote, referring to the outgoing FTC chair. If the whistleblower could preempt Ferguson’s tenure and garner scrutiny over the Amazon deal, then perhaps, he reasoned, the FTC would take his complaint seriously.

But despite the Washington Post article being thorough and well-reported, it was swallowed up by other news. On inauguration day, Amazon owner (and Washington Post owner) Jeff Bezos appeared on the dais with Trump. The whistleblower’s hopes turned to apprehension.

In the year since, some of the whistleblower’s fears have come to fruition. The FTC hasn’t given him any updates on the complaint he filed. He’s warily watched as Amazon—with Covariant’s talent and tech on board—rolled out one million robots. Internal strategy documents obtained by the New York Times indicated that Amazon has considered someday automating 75 percent of its operations, which would translate to not hiring hundreds of thousands of workers it would otherwise need to meet customers’ demands. Meanwhile, the available evidence suggests Covariant no longer has an American headquarters, is down to a small number of overseas employees, and may or may not be operating at all; if that’s the case, it would be a damning rebuttal to Amazon’s reverse acquihire, which is premised on Covariant continuing to exist as a business that offers its technology to other e-commerce companies.

The whistleblower, who requested anonymity due to fear of repercussions from Amazon and Covariant, was compelled to speak out again about his concerns. In an effort to corroborate his allegations, we spoke with two other former Covariant employees, who were granted anonymity to speak freely. We additionally reviewed internal documents, photos, and a video of Covariant’s current CEO, Ted Stinson, where he discusses the Amazon deal. We also interviewed former FTC sources and other experts, and sent a list of detailed questions to Amazon, Covariant, and the FTC.

Covariant was founded in 2017 by Pieter Abbeel, Peter Chen, Rocky Duan, and Tianhao Zhang, four of the leading engineering minds in the robotics space. Abbeel, Chen, and Duan previously worked at OpenAI as research scientists, according to their LinkedIn profiles. Covariant was at the forefront of improving dexterous robots—basically, robots that complete sophisticated tasks usually left to humans, like manipulating delicate fruit or strategically placing boxes to maximize storage space. Those improvements came from Covariant Brain, an AI-powered platform that automates inventory tasks performed by robots. Covariant Brain got the attention of warehouse integrators like KNAPP, and later, the attention of companies in other industries.

Covariant secured $7 million in seed funding, which it upped to $222 million in total funding by 2023, according to its website. As Covariant’s funding grew, so did its footprint. In 2022, the company expanded from its headquarters in Emeryville, California (near Oakland) to an office in London, too. Two former employees who spoke to Hard Reset ballparked having more than 100 colleagues, including in Europe.

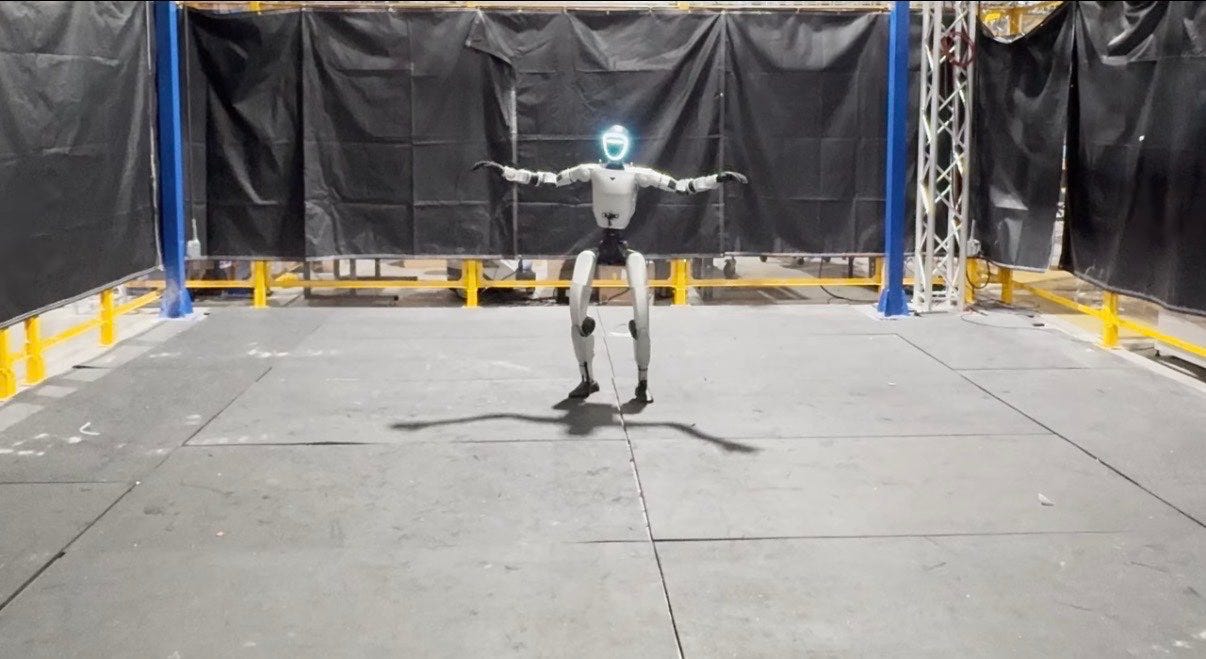

In March 2024, Covariant announced RFM-1—a “Robotics Foundation Model” that marked a major leap forward for Covariant Brain, because it was designed to give “robots the human-like ability to reason on the fly.” By Covariant’s own admission, RFM-1 still needed lots of tweaking, but it was indisputably impressive. It’s not difficult to ascertain why a company like Amazon would be interested in licensing that sort of technology.

The problem for Amazon was that Lina Khan was still FTC chair in 2024, and until the conclusion of the November 2024 presidential election, it was uncertain whether the next administration would take a more favorable approach to Big Tech and mergers. The FTC was extremely understaffed during Khan’s tenure, as has been the case for decades. But Khan and her team were focused on mergers and acquisitions, and one of the tools they had at their disposal was the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act. Under the HSR Act, companies are supposed to alert the FTC if they are planning a large merger or acquisition (anything over $133.9 million). Afterwards, the FTC has up to 30 days to decide whether to investigate a deal for monopolistic implications. An FTC investigation can delay a deal’s close by anywhere from six to 15 months, or lead to the government suing to block the deal altogether, according to an antitrust lawyer who previously worked in merger enforcement at the FTC and spoke to Hard Reset.

To avoid alerting the government under the HSR Act, Big Tech has turned to reverse acquihires, which don’t technically involve absorbing an entire company—just its key talent and technology. Alexandros Kazimirov, a legal scholar and former fellow at the American Antitrust Institute, said that reverse acquihires are an evolution of common business practices in the tech world over the last fifteen years, and they are not inherently illegal. But “if the company fails immediately after you buy it, that looks bad,” he added.

The first prominent example of a reverse acquihire was in March 2024, when Microsoft hired the founders of AI startup Inflection; Microsoft also reportedly snagged most of Inflection’s staff, and paid for the “nonexclusive” rights to Inflection’s tech. Amazon followed suit by initiating a similar-sounding arrangement with startup Adept in June 2024. The Inflection deal ended up drawing scrutiny from the FTC. “When high-profile acquihires in the tech industry occurred, they were on our radar,” said Tim Chinenov, an FTC technologist during Khan’s tenure.

Having already swung one reverse acquihire, Amazon was emboldened to try a second reverse acquihire with Covariant. According to Covariant CEO Stinson, that was the only option for Amazon and Covariant. “The FTC is blocking these transactions,” he said during the video call obtained by Hard Reset. “Go back and read the history of what they have done in recent transactions. They’re blocking them.” Stinson noted that lawyers involved in the deal—who were paid “multiple millions,” he lamented—believed “there was only one path if you wanted to acquire” Covariant. He seemed to be referring to a reverse acquihire.

The Amazon-Covariant deal was made official on August 30, 2024. Abbeel, Chen, and Duan departed for the Amazon Robotics team, and brought a portion of Covariant employees with them. Zhang and Stinson—who was formerly Covariant’s COO—took over as co-leaders of the “new” Covariant. Mass layoffs came next. The “new” Covariant was the result of a merger with a shell corporation called Variation Merger Co., which existed for just a few days before the Amazon deal was announced.

Terms of the Amazon deal circulated to shareholders, including the whistleblower, in a hefty document. “Imagine you receive an email from PNC Bank that suddenly gives you hundreds of pages of documents to sign with lots of fine print,” the whistleblower says. “The employee Slack you’re a part of is confused. They tell you to sign, get your money, and go away. My first thought was: what don’t they want me to know?”

The whistleblower dug through the document, which Hard Reset also obtained. Although Covariant was merging with the newly-formed shell company, accepting a payout required releasing Amazon from all potential legal claims. Signees were also subject to tight confidentiality provisions. Up front, Amazon paid the “new” Covariant $380 million in exchange for Covariant’s talent pool and a “nonexclusive license” of its technology—AI models, robotics software, patents, and training data gathered over years of operation.

Amazon’s agreement with “new” Covariant called for a second, $20 million payment to Covariant shareholders a year after the deal was signed. In the whistleblower’s view, this was a way of establishing deniability about the terms of a supposedly nonexclusive agreement. Covariant would stay alive, albeit on life support, as evidence that it could still license its tech to companies besides Amazon.

Stinson seemed to confirm as much on at least three occasions during the video obtained by Hard Reset. “Because of this structure, Covariant not only could exist—it must exist,” he said. “In other words, it has to continue for some time in the future.” Later, he said, “Covariant needs to exist for some material period of time.” To put an even finer point on it, he added, “Amazon wants to have their cake and eat it too. They really didn’t want us to be able to use this technology, but they knew Covariant had to exist, so they couldn’t completely say, you know, ‘You’re crippled.’”

Portions of Stinson’s remarks were previously reported on by the Washington Post, which reached out to Amazon for comment. In Amazon’s telling, it didn’t absorb Covariant or its tech in full. It wasn’t being anticompetitive. Covariant was welcome to—encouraged to—stick around and strike more deals, as an Amazon spokesperson told the Washington Post.

“Amazon spokeswoman Angie Quennell said a premerger filing was not required because the company only took a nonexclusive license,” the Post reported. “She said it did not want Covariant to stop being competitive, noting that some employees remained there.”

(Amazon did not respond to emailed questions from Hard Reset.)

Stinson himself threw cold water on the idea of remaining all that competitive, or even financially solvent, after the Amazon deal. “I think we’ve got a decent shot at pulling off one or two of these license deals,” he said on the video obtained by Hard Reset. “But they’ll be single-digit millions, maybe double-digit millions. They’ll be a fraction of what Amazon paid, is my best guess.”

He said that a valuation firm put the “new” Covariant’s value somewhere between “zero” and “single-digit to maybe low double-digit millions.” He described Covariant as having the “risk profile of a seed or an early-stage company,” conceding that it was “very speculative that you could get the money out of it.”

With the help of his attorney John Tye, who co-founded the Whistleblower Aid legal foundation, the whistleblower filed a complaint to the FTC and other relevant agencies in early January 2025. “Amazon obviously has a dominant position in e-commerce; it used that dominant position to impose questionable terms on Covariant; the deal allows Amazon to expand its dominant position to advanced robotics far beyond the realm of e-commerce,” the complaint stated.

The Washington Post article about the whistleblower complaint ran later that month. On March 7, the whistleblower met with the FTC to discuss the evidence he Tye had gathered. To the whistleblower, the evidence was damning and persuasive. He was cautiously optimistic. It seemed like a good sign that the FTC was still meeting with him under new leadership.

And then on March 18, President Trump fired Rebecca Slaughter and Alvaro Bedoya, two Democratic members of the five-member FTC board. (Both sued; the lawsuit is ongoing.) An exodus ensued. The FTC’s office of technology hemorrhaged staff and only has a few people left, according to a recent report from The Capitol Forum. The whistleblower says he hasn’t heard from the FTC since that March meeting, despite Tye reaching back out to the agency. The FTC did not respond to emailed questions and a request for comment from Hard Reset.

Amazon, on the other hand, has seemingly made quick work of Covariant’s talent pool and tech.

Covariant’s former brain trust has found a home with Amazon’s Frontier AI and Robotics team. FAR, as it’s better known, is merging the AI tools developed by Covariant researchers with the billions of historical and live data points accumulated via Amazon’s existing robots, which handle e-commerce inventory.

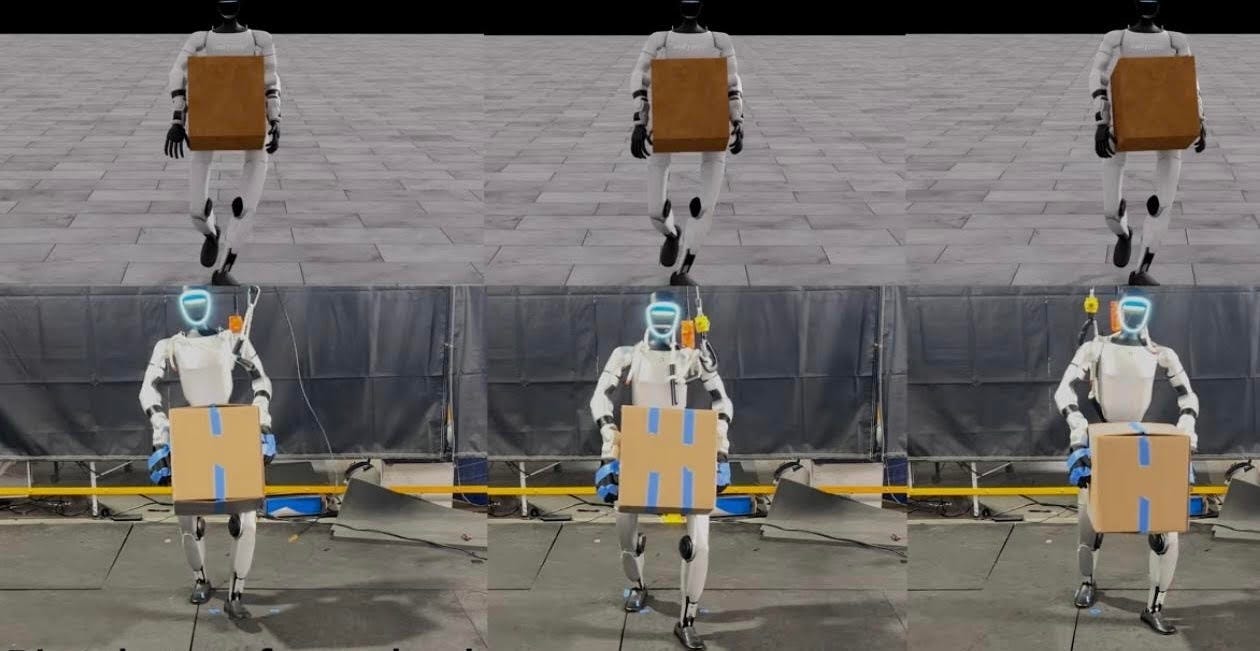

Before the Covariant deal, Amazon’s robots, including the Robin and Cardinal models, were only capable of picking up uniform boxes and cases, requiring minimal AI capabilities. After the deal with Covariant, Amazon’s robotics timeline appears to have sped up. In October 2025, the Amazon Robotics team reportedly launched a six-arm robot called Blue Jay; according to Amazon, the Blue Jay model “moved from concept to production in just over a year—a process that formerly took three or more years for earlier Amazon systems” like Robin and Cardinal. The report attributed the shortened development timeline to “advancements in AI,” and included a glowing quote about Covariant from Aaron Parness, Amazon Robotics’ director of applied science.

“We’ve been working with the folks at Covariant on how to orchestrate our robotic work cells,” Parness said. “How to use their models, but also their model infrastructure to go faster in going from a prototype to a product or going from a concept to something we have in the field. This is something Blue Jay is a great example of.”

It remains to be seen precisely how many jobs will be impacted by Amazon’s robotics developments. As the second-biggest employer in the United States behind Walmart, Amazon is considering automating 75 percent of its operations, according to the internal strategy documents obtained by the New York Times. It’s unclear if the strategy documents accounted for the possible production of humanoids. According to a 2024 report from Goldman Sachs, 6.5 million industrial and consumer humanoid robots could be deployed in less than a decade in a “bull” scenario, while over 11 million humanoids could be deployed in a “blue sky” scenario. And research firm Forrester predicts that 6.1% of U.S. jobs will be lost by 2030 due to AI and automation, equating to 10.4 million jobs.

A former Covariant employee expressed concerns about what Amazon and automation might have in store for labor. “I’m disappointed that the tech industry has become, in my perspective, so anti-competitive that startup entrepreneurs recognize their best pathway to success is getting acquihired,” they told Hard Reset. “In the Covariant/Amazon case, what does the future of warehouses look like if it’s just Amazon having AI-powered robots in the warehouse and everyone else is using human workers? What does that mean to society in how you regulate that?”

Roughly a year and a half since the deal with Amazon was announced, it’s hard to tell what’s left of Covariant. A former Covariant worker with direct knowledge of the situation told Hard Reset that the Emeryville headquarters was emptied out within months of the Amazon deal closing. Robot parts were sold off and donated, they said. An internal message sent by another former Covariant worker, dated to late 2024, also noted that robot parts were being sold off and donated. On a recent visit, it appeared to be vacant inside the headquarters.

On the video obtained by Hard Reset, Stinson said the company was down to roughly 20 people, many of whom were based in China. Since then, two of the company’s remaining overseas higher-ups, Antoine Pare and Wei Mu, both left the company. No one from Covariant’s press email responded to Hard Reset’s questions, including whether the “new” company has executed any licensing agreements. Stinson’s LinkedIn still lists him as CEO. He did not respond to emailed questions from Hard Reset.

Kazimirov, the antitrust expert, examined the whistleblower’s allegations about the Covariant deal and said he wasn’t surprised Amazon didn’t try for an exclusive license. Nor was it surprising to him that Amazon wanted to “prevent [Covariant’s] technology from falling into the hands of a competitor.” But he wondered why Covariant’s founders agreed to the deal. “That Amazon planned and carried out a fairly aggressive quasi-merger is not surprising, but that Covariant’s founders went along with it, disregarding the interests of their investors, fellow founders, and employees, makes me question their motive—namely, if they exercised business judgment in good faith,” he told Hard Reset.

Covariant partners that once touted their business arrangements with the robotics company have gone silent. Two such partners, KNAPP and Radial, did not respond to requests for comment. A spokesperson for Otto Group, an e-commerce conglomerate based in Europe, wrote that they “continue to deploy Covariant,” but declined to answer specific questions about how Covariant’s deal with Amazon affected their own business relationship—including whether Otto Group ultimately deployed more than 100 “AI robotics stations” at their fulfillment centers, as was the stated goal in 2023.

Covariant’s social media hasn’t been updated since the Amazon deal was announced. Neither has Covariant’s “press” page. The latest post on the site, also from August 30, said that Zhang and Stinson were staying on to create “a strong foundation for continued success as they lead Covariant into an exciting new phase of growth.”

The post continued: “Looking forward, we’re incredibly excited about what’s ahead for Covariant and truly believe in the transformative power of AI Robotics.”

The whistleblower believes in the transformative power of AI robotics, too. Absent regulatory actions, though, he worries that power will be disproportionately wielded by Amazon.

“When we look at other humanoid robotics companies like Boston Dynamics, they have marketing videos and investment, but it’s still a fraction of what Amazon can do,” the whistleblower said. “The impact of this reverse acquihire will be broader than just the product that Covariant already made.”

Jan. 22: An earlier version of this story misstated the timing of Alexandros Kazimirov’s work at the American Antitrust Institute. He is a former fellow there, not a current one.

I thought this piece had an elaborate joke lede and kept scrolling for the punchline. Then I found myself at the end of the article. The “human-like reasoning” line from the subhead is found only once in the article, when it directly quotes Covariant’s marketing materials and parrots its claims with no scrutiny. I thought Hard Reset was above clickbait but I was proven wrong.

auughhhh😖