Q&A: The Man Whose Model Predicted The Mess We’re In

Jack A. Goldstone was dismissed when he theorized, more than 30 years ago, that rising inequality could make the U.S. vulnerable to political chaos. He wishes he hadn’t been vindicated.

We’ve talked a bit in this newsletter over the months about keeping our eye on the plot and how the mainstream media — of which I am a former card-carrying member — doesn’t always do a good job at keeping the big story front and center. Instead of a consistent focus on theme and an orientation of news stories fleshing it out, the industry is often reactive, playing catch-up with the endless scroll of eye-catching news while missing coverage that actually builds understanding and perspective.

This big story to me has always been inequality. As a journalist and observer, it just seemed to hover behind every narrative, invisible but perceptible, an explanation for why normal frustrations and challenges were turning so toxic, nasty, and explosive. It is a source of that bad energy. And dark sorcerers out there are using it to their advantage, instead of ameliorating it.

It’s been nearly 15 years since Occupy Wall Street exposed what a potent issue this could be for everyday people and *cough* voters. But the issue has never been taken seriously enough by elites, institutions like the media, and of course, elected officials to actually do something about it. So it keeps getting worse. And worse. And worse.

But I’m no scholar. The feeling I had about it amounted to an educated hunch. I found myself at a loss in the middle of a debate with a friend over this a few years ago, as I tried to argue how inequality could help explain everything going on politically. I couldn’t quite answer my friend’s simple query of, “Why?”

Reading another newsletter recently, Taylor Lorenz’s excellent User Mag, I happened across a stunningly clear-eyed piece from two political scientists that answered that question, with rigor and depth. The authors laid out the mechanisms by which excessive inequality — and the greedy, defensive actions of the elite — can be a key ingredient in the degradation of a political system. “Welcome to the ‘Turbulent Twenties,’” the piece, which was published in Noema in 2020, was headlined. “We predicted political upheaval in America in the 2020s. This is why it’s here.”

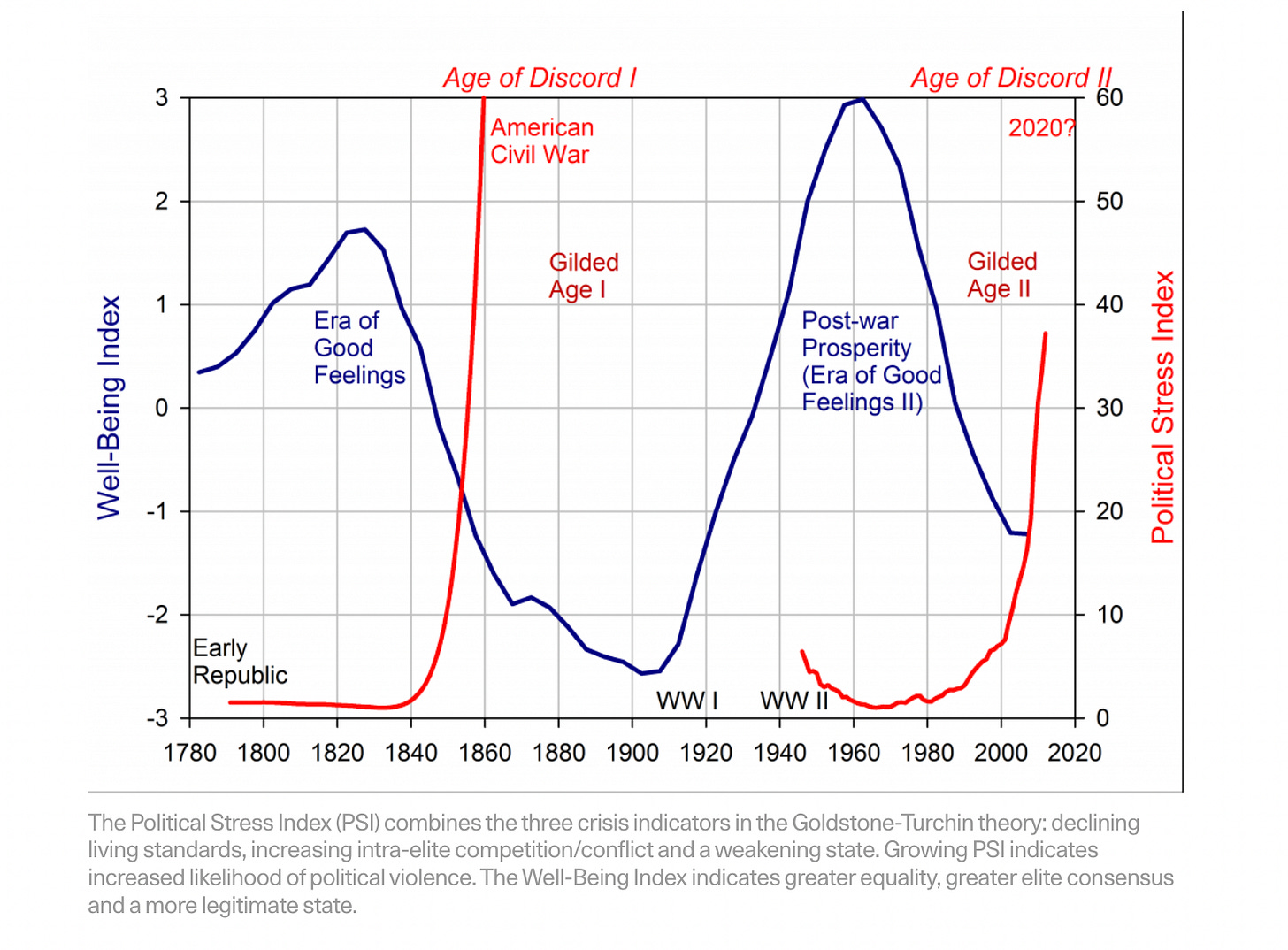

The article, by George Mason public policy professor Jack A. Goldstone and Peter Turchin, a social scientist at the Complexity Science Hub in Vienna, described a model they had developed which could draw a through-line from political chaos and historical revolutions in places like Russia and China to where we were today. When applied to our society right now, the model flashes major warning signs, showing us at the greatest risk of political crisis since the lead-up to the Civil War. And it’s not vague about where blame should be placed: inequality and the people who help push that system forward.

“Selfish elites lead the way to revolutions,” the two wrote. “They create simmering conditions of greater inequality and declining effectiveness of, and respect for, government.”

Since the 1970s, [the social] contract has unraveled, in favor of a contract between government and business that has underfunded public services but generously rewarded capital gains and corporate profits.

While this new neoliberal contract has, in some periods, produced economic growth and gains in employment, growth has generally been slower and far more unequal than it was in the first three postwar decades. In the last twenty years, real median household income has stagnated, while the loss of high-paying blue-collar jobs to technology and globalization has meant a decline in real wages for many workers, especially less educated men.

As a result, American politics has fallen into a pattern that is characteristic of many developing countries, where one portion of the elite seeks to win support from the working classes not by sharing the wealth or by expanding public services and making sacrifices to increase the common good, but by persuading the working classes that they are beset by enemies who hate them (liberal elites, minorities, illegal immigrants) and want to take away what little they have.

Sound familiar?

Even more impressive than developing a cohesive model that can apply across both geographies and history, is that the two of them had seen this coming in the U.S. long in advance.

Goldstone had laid out the model, which he coined the Demographic-Structural Theory, in a 1991 book he published as a 20-something academic, using data on things like inequality, political polarization and structural issues like national debt to predict instability. Even back then, Goldstone predicted that America was likely to get a populist leader who would sow conflict. Turchin later took the theory further, using it in 2010 to find that the U.S. was experiencing its biggest vulnerability to political crisis since the mid-1800s, and that the U.S. and Western Europe would experience a “Turbulent Twenties” marked by instability.

Reading through their work, I was stunned by how prescient it was. I called Goldstone, who is based in the D.C. area, to discuss. He said his model — and what it means for the U.S. — has finally started getting more attention in Washington recently after years when he was only consulted about unstable foreign countries.

Hard Reset: Tell me about where the first seeds of the idea that became the model you developed to predict political instability came from?

Jack A. Goldstone: I had been looking to understand why revolutions occur. Most people approached it from the bottom up: Why do people rebel against their government? What leads to mass discontent?

I kind of figured that there’s always people who are unhappy. The real question to me was why did that unhappiness come together at certain times with a weakness or inability of the government to hold together.

The government has the armed forces, they have the police, they usually have most of the business community on their side. It should not be possible to overthrow a government. But the more I studied, the more I realized it only happens when the government is not only weak by itself, that it’s got some financial problems or legitimacy issues, but also when the elite, the business people, the military officers, the government officials, the community and labor leaders — people who usually have a vested interest in the existing order — start to turn against the government too.

As the country gets richer, it’s quite normal for some parts of the population to get richer first. Growing inequality is often an accompaniment of economic growth. But in order for that inequality to not draw anger and resentment, and not to weaken the government, it’s necessary for the newly rich to be supportive of society as a whole. Recognize that the goal is to strengthen society, and allow taxation of their wealth. They endow universities, parks or museums so that their wealth is creating some public benefit.

But there’s another outcome. And that is when the rich feel that their society doesn’t need their wealth, and is in fact wasting their tax money. And then the inequality is accompanied by what I call the rise of “selfish elites.” And when you see this, you see people who have made it pulling up the ladders behind them so that the rate of social mobility drops and ordinary people find it much harder to get ahead. You see the share of income being paid as taxation by the elites starts to drop as they find ways to hide their wealth. And that selfish elite condition is one in which the rich kind of pull away, go to their private islands, fly their private jets to their private communities and figure that hey, we’re the superman, our wealth is earned and all of it should be ours. And if the rest of society is suffering too badly, inequality becomes threatening to the social order and creates the way for democratic backsliding, Civil War, regional uprisings, and any number of state breakdowns.

HR: Seems like you’re describing a society I know well. What is your assessment of where we are at right now in the U.S.?

JG: The United States is the most vulnerable to political breakdown it’s been since the Civil War. And I say that because we see all these patterns. The government has out-of-control debt and is trying to cut back on vital services, everything from healthcare to national parks, to regulation to keep a safe environment, essentially saying, no, we can’t afford it even though we’re richer as a society than we’ve ever been.

The rich are fighting tooth and nail to reduce their taxes. We saw this in the Big Beautiful Bill that was just passed, but it’s a pattern that’s really been going on for decades. The federal government has run a deficit every year for almost the past 40 years. It’s usually been about 3% of GDP. And so you run that for 40 years and the national debt is going to be over a hundred percent of GDP. That’s where we are now. But instead of saying we need to restore funding so that our government can function, the rich are saying, “No, we don’t want the government to function. What matters is getting the government off our backs.”

The top 1% has a larger fraction of national wealth under its control than it’s had for over a hundred years. I’m not saying tax the rich is the answer to everything, but if the rich simply paid the same taxes as ordinary Americans, if everybody paid 25% of income, that would get rid of our deficit problem and we could afford social security, Medicare, health insurance, all of that. The problem is they don’t. You remember Buffet saying his secretary pays a higher marginal rate on her income than he does. That’s not healthy for this country. So we’re in a bad situation. The government is underfinanced and chronically in debt and has lost enormous trust and legitimacy among the broader population.

HR: The early 1990s were marked by a period of optimism — arrogance perhaps — after the fall of the Soviet Union, that theorized that history was “over” and neoliberal capitalism was some sort of final societal order. Your predictions that the U.S. was vulnerable swam against that tide. How were they received then?

JG: Back then I said America is showing signs of moving in the direction of France before the French Revolution. We were seeing signs of selfish elites, we’re seeing signs of growing government debt, we’re seeing signs of lagging real wages for most workers. I was worried even then. I said, we’re heading for another wave of protectionism, possible authoritarianism, possible civil conflict.

I was concerned that if governments didn’t pay attention we would have another wave of institutions losing legitimacy and crumbling. I don’t know if that would be civil conflict or the rise of strong men dictatorships. But of course I was dismissed as ridiculous.

People said, yes, we can see how your model makes sense for pre-industrial regimes, but this is a different world now.

HR: Was it just your data that led you to that conclusion or did you initially have a little bit of a sixth sense telling you that there was something wrong within the system before you studied it?

JG: I’ll be honest, my gut said, well, it doesn’t have to be that way and it probably won’t, so I hope I’m wrong. But the data said this is what’s happening.

Years later, when President Obama was elected, I hoped that he might be able to change the direction of things, maybe like Roosevelt had done in the 1930s and build a coalition that would rein in elite greed and redirect national wealth in the direction of non-college educated workers, ordinary Americans, and white collar people. But it didn’t happen.

Right now I feel like a novelist who wrote a book of fiction 20 years ago about their own death thinking it wouldn’t happen. And now I start to see the events take place day by day. It’s very unsettling, and now my gut gives me a lot of difficulty.

HR: Politically how do you identify and has that changed over the years?

JG: I’ve always viewed myself as an independent. I’ve consulted for Republican and Democratic administrations. I’ve been critical of Democratic and Republican leaders throughout.

HR: When a society is headed in this direction, where does it lead?

JG: Well, there’s always a crisis because you get to a point where you have multiple fault lines. You have elites that can’t work together because they’re so deeply polarized and hate each other. You have a government that is struggling financially and is looking to change what it does or how it operates. And you have people who are ready to jump the whole thing because for a couple of decades they’ve felt like they’re falling behind the rich and the government doesn’t care about them, and everything they hope for themselves and their kids and their future is being frittered away. That combination is going to lead to a crisis.

HR: Do you view the current state of the tech revolution — and the massive wealth but also structural issues it’s raised — as something that is unique historically?

JG: No. There’s a reason that we had trust-busters in America in the early 20th century when large corporations called out Pinkertons to mow down striking workers with bullets. Americans recoiled and said, corporate power is going too far. Teddy Roosevelt was elected to reduce the power of corporate behemoths. Even titans like Rockefeller had their empire broken up. This happens throughout history that once a very wealthy group of oligarchs or plutocrats become so powerful that they have no regard for the lives of their workers, societies either rise up against them or the oligarchs unite behind a strong man and support the move toward authoritarianism. It’s nothing new.

HR: What has your research shown you about how these moments of discord end?

JG: Any number of analysts including Peter Turchin, but others as well like Walter Scheidel at Stanford, argue that other than this drift to authoritarianism, the only way this changes is if you get a crisis that threatens the existence of society.

If you get a major economic collapse, Depression-style with a quarter of the population out of work, or you get a war that requires total mobilization of the society for warfare under that kind of crisis, elites don’t have the leverage to resist taxation, and governments need to have everybody on their side, otherwise they can’t fight the war or rebuild the economy. And so under those conditions, you get people searching for how to work together to build new institutions. This is why Europe and America did so well after World War II.

HR: Were you surprised that the pandemic we all just lived through didn’t provide a prompt for that? There was some talk about how it was going to be that. And instead it went in the opposite direction.

JG: I looked at this carefully. The global pandemic of 1918 killed about 10% of the population. Even that wasn’t disastrous enough to force societies to change. COVID killed maybe 1% of the population. We’re not talking about the plague, which killed 30% or more. 1% of the population is awful if you know somebody who’s in that 1%. But frankly if you look at the curves for the economy, employment, etc you see a one-year, two-year spike in recovery, and then you get back on the same path we were on before. So COVID was not a big enough crisis to force us to reevaluate how our society is organized.

HR: I remember during maybe the late Obama years leading up to Trump’s first term, you would read these news reports from Davos or other events where people in these super elite circles were starting to talk openly about how inequality and a growing distrust about institutions was causing instability. They were saying, “We might have to go do something about this, or someday they’re going to come to our houses with pitchforks.” That too has gone the other way now. These folks seem to be saying, “They’re going to come to my house, and that’s why I’m going to build an underground bunker. That’s why I’m going to Mars. That’s why I’m moving to an autonomous state in Central America.” And it feels like there was a moment there to address this stuff, but it’s passed.

JG: There have been a few potential inflection movements when global elites could have said this trend towards corporate greed and financialization of everything and greater accumulation of wealth and stagnant real wages — that’s not going to be good for us in the long run. So let’s think about different approaches. But that didn’t last.

HR: You wrote a piece on the eve of the 2020 election that noted the potential for election related violence and disruption, some of which, obviously came to pass. But then the new administration got elected and there was a moment where it seemed like there was going to be a restoration of justice and rule of law, and the sanctity of elections and all of that. Not to mention Biden’s appeals during that time, to re-invigorate bipartisanship and cooperation and all of that. Why did that project fail so spectacularly?

JG: The underlying trends were in the direction of political decay. That is for the last 40 odd years, real wages, especially for non-college educated men, which is the largest single group, have lagged behind growing wealth and professional incomes. Under Biden, there were some improvements in the minimum wage and so on, but you have these long-term trends of inequality and diminishing social mobility that have been a pressure cooker for anger and grief.

There are two ways that political leaders can approach that pressure cooker. You can stoke the fire to try and take advantage of it and get more power for yourself. This is what autocrats have done in Eastern Europe, increasingly in Western Europe, and increasingly here. The other way to deal with that pressure cooker is to look for ways to release the pressure and change things.

Biden, to his credit, did want to release the pressure. But Democrats couldn’t get together on a single message. They got bogged down in identity politics. They got overwhelmed by the crisis at the border and didn’t respond quickly enough, and still never took responsibility. And so the Democrats, even though they tried to do the right thing, and I think Biden did have some initial success, they weren’t able to move enough of America into a framework of let’s all work together to fix this.

HR: Thanks for your time, professor.

See you all next week.

I love that guys covered Peter here. His work is very important for anyone that needs to understand the cycle of history

Perhaps a better thought experiment should be: maybe they're doing it on purpose.

Also, there's the whole gini-coefficient work on inequality you could look into.

I'm a big fan of Turchin's work, but actually if you dig down into the details, you'll find that academia only offers macro lens analysis and recommendations. It's unfortunately one of the drawbacks in today's world. They don't pull their punches and name names. Turchin's books are great until you read his proposals for solutions. Then it's more of highlighting leaders who took away the wealth pump from elites and redistributed access. And as you can imagine, said like this it sounds easy, but apply it to the real world and all of a sudden...

The good news is that Turchin says society is able to correct it's mistakes around 1/3 of the time. The bad news is civilizations and empires go ka-put in the other 2/3s.